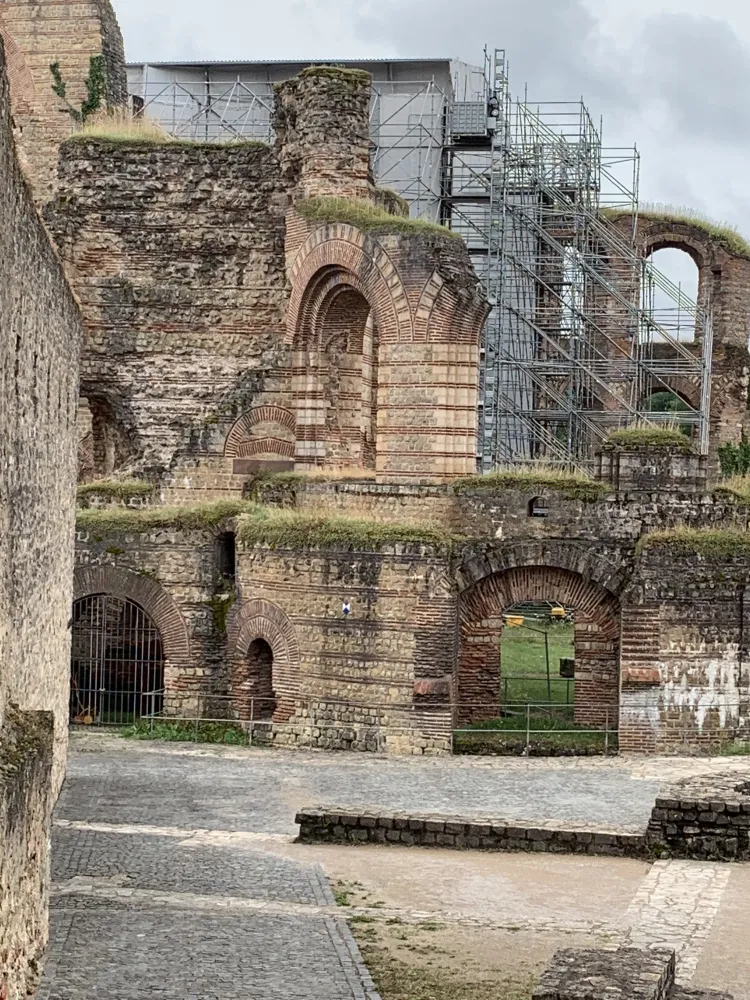

In the Roman city of Trier, I visited one of its main attractions, the Imperial Baths, which were planned as one of the largest bathing facilities in the Roman Empire. The late antique building represents the period from the 4th to 5th centuries, when Trier was the imperial residence and thus one of the most important metropolises of the Roman Empire. The Imperial Baths, with their bathing hall, sauna, massage rooms, and promenade halls, were intended to serve as a place of relaxation for the Roman elite. However, they were never completed in their originally planned function. They have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and I set out to explore the mighty ruins with their underground labyrinth. My first stop took me to the warm bath hall, the caledarium, which is now occasionally used for events and can seat up to 650 people. From there, I went to the cold bath area. In Roman times, a visit to the thermal baths began with cleansing the skin with oil, followed by baths of varying temperatures, massages, and sweat baths. Medical treatments and operations also took place in the thermal baths. This explains the complex sequence of rooms in the Imperial Baths. The largest hall was originally intended to be a cold bath, or frigidarium. After the original construction plan was abandoned, it was completely demolished. I marveled at the walls visible today on the site, which were reconstructed according to this plan. The same applies to the wide curved wall, where one of the water basins, piscina I, was planned. I then walked to the intermediate wing. This formed the transition as a lukewarm wing, tepidarium, with bathing rooms on both sides of the rotunda between the warm and unheated bathing areas. Floor and wall heating was planned for the round hall. After the cold bath wing was demolished, the rotunda became the new entrance hall. I discovered the original door thresholds and felt transported back to a bygone era. The second main hall of the thermal baths was equipped with underfloor heating and was intended as a warm bath, caldarium. Here, too, there was a semicircular, heated water basin, piscina II, in each apse. I recognized a whole series of fireplaces around the large apse, which were intended for heating under the water basin. These were fired outside the room. The hot air could circulate under the pool and the floor. Today’s floor is below the level of the ancient floor. Because the underfloor heating, hypocaustum, alone would not have been sufficient to achieve the desired bathing temperature of 40 °C, additional boiler stoves were necessary for hot water production. They were to be installed in the corner buildings planned as boiler houses. This part of the building owes its good state of preservation to its continued use in the Middle Ages. A fortified residential tower, the Alderburg, was later built into the corner of the Roman caldarium. When the medieval city wall was extended to the Alderburg in the 12th century, the large Roman window arches were bricked up. In the southern apse, a city gate, Alderport, was set up with one of the Roman windows as a passageway. I reached the underground supply tract via a staircase from the so-called “public level.” In ancient times, the supply tract was not intended for public use. For the operation and maintenance of the thermal baths, there was an elaborate system of service corridors below floor level. There, the staff had access to numerous chambers with fireplaces, praefurnium, and underfloor heating. The sewage channels, cloaca, which were also necessary for the operation of the thermal baths, run for long distances directly under the service corridors. The drain belongs to the semicircular basin of the frigidarium. The water supply for the entire complex was to be provided by a 13-kilometer-long pipeline from the Ruwer River via a branch at the amphitheater. From the semicircular corridor, I looked into a preserved excavation site, the private bath of the town house, domus, from the time before the baths were built. The small brick pillars that I saw on the right in the niche were part of the underfloor heating, hypocaustum, and supported the actual floor. After leaving the underground part of the complex, I reached the small bath, balneum. This smaller bathing complex was built after the thermal baths project was finally abandoned in the late 4th century. Its front faced today’s palace garden. An open portico with columns bordered the neighboring Roman road. Although the thermal baths adjoin the Basilica of Constantine, they face the forum in the direction of the Moselle. The main front with the entrance faced today’s Weberbach street. From there, open colonnades, porticus, led to a large open area for sports and games, the palaestra. After the thermal baths project was abandoned, this space was expanded and used for other purposes. I was fascinated by the Imperial Baths, which can be described more as a building ruin, as they were never used for their intended purpose. Unfortunately, the project came to a standstill when Constantine I shifted his major political activities to the East. It was not until the 360s that construction work was resumed under Valentinian I. The emperor had part of the complex demolished and the rest completed as a reception or drill hall without the installations for bathing. The barracks-like conversions around the inner courtyard date from this period. In the Middle Ages, a noble family from Trier settled in the dilapidated main building and converted it into Alderburg Castle. The Church of St. Gervasius and the Agnetenkloster monastery were built in another part of the ruins. Due to this dense overbuilding, the overall architectural concept of the thermal baths was not recognized until the beginning of the 20th century. It was only after the destruction of World War II that the formerly built-up site could be excavated and extensively investigated between 1960 and 1966. Today, the complex belongs to the state of Rhineland-Palatinate. I was impressed by the thermal baths, which I was able to explore on my own thanks to a multimedia guide and experience firsthand by walking through the upper and lower parts of the baths. The adjoining exhibition area with models and a film animation brought the thermal baths to life for me once again. The Imperial Baths are a wonderful remnant of antiquity and well worth seeing. I was overwhelmed by this sight and set off for the next UNESCO World Heritage Site in Trier, the Porta Nigra, the Roman city gate of Trier.